The open-plan office is the workplace equivalent of a badly thought-out surprise party: loud, disorienting, and leaving you wondering who thought this was a good idea. Promising collaboration, creativity, and egalitarianism, it instead delivers distraction, performance anxiety, and the undeniable urge to hide behind a fake potted plant.

But as infuriating as they are, open-plan offices aren’t just about poor design or cost-cutting. They reflect deeper dynamics of power, control, and social interaction—issues that would make any sociologist salivate. If Jeremy Bentham, Michel Foucault, Karl Marx, Erving Goffman, Pierre Bourdieu, and Max Weber all walked into an open-plan office (a scene I would pay to watch), they would likely find themselves nodding knowingly. This, they’d say, is the logical endpoint of their theories, wrapped in Ikea furniture and bathed in fluorescent light.

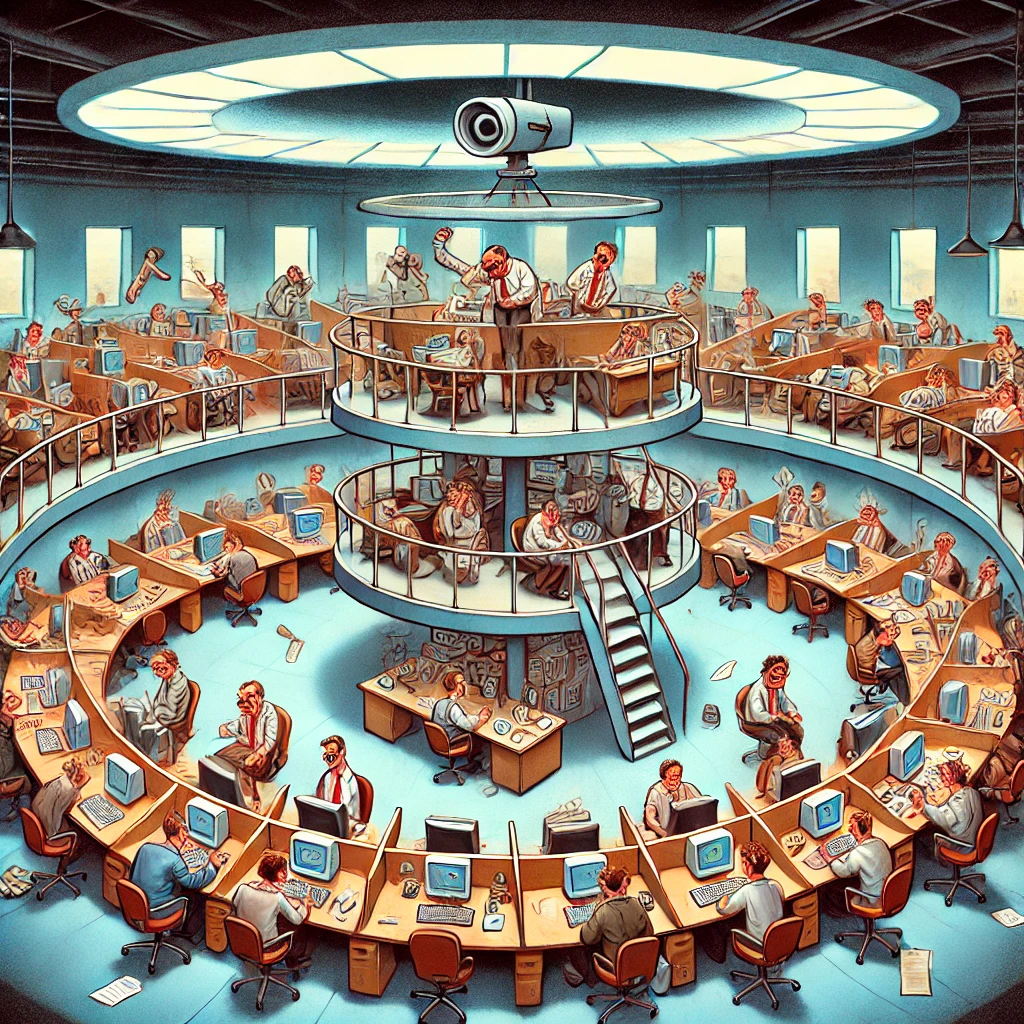

Let’s start with Bentham. His Panopticon, designed in the 18th century, was meant to revolutionise prison systems. Picture a circular structure with cells lining the edges and a central tower from which guards could observe inmates. The brilliance—or horror—of the design lay in its asymmetry: inmates couldn’t see the guards, so they never knew if they were being watched. The mere possibility of surveillance was enough to make them self-regulate their behaviour. Bentham, ever the utilitarian, thought this was genius. After all, why waste resources on actual observation when you can let paranoia do the heavy lifting?

Fast-forward a couple of centuries, and the open-plan office takes Bentham’s principles to their logical, corporate conclusion. Here, the central tower is replaced by the omnipresent gaze of managers and colleagues. There may not be an actual guard watching your every move, but the lack of walls ensures that someone might be looking. Thinking of checking your phone? Better angle it discreetly. Contemplating a quick chat with a coworker? Keep it just loud enough to sound work-related. Open-plan offices are a stage where everyone is an actor, and the only script is “Look Busy.”

Foucault, ever the party-pooper, would take this one step further. In Discipline and Punish, he expanded on Bentham’s Panopticon, arguing that surveillance isn’t just about control—it’s about shaping behaviour. The Panopticon, he said, is a metaphor for modern power structures where people internalise surveillance, regulating themselves even when no one is watching. The open-plan office, then, isn’t just a workplace; it’s a social experiment where workers become both the observed and the enforcers of their own discipline.

Every glance from a colleague, every passing manager, every accidental eye contact becomes a micro-interaction of control. Even the benign act of stretching at your desk feels like a performance. Are you stretching because you’re diligent and focused? Or is it a lazy stretch, signalling you’ve mentally checked out? The open-plan office turns workers into amateur sociologists, constantly interpreting and misinterpreting each other’s behaviour.

Marx, meanwhile, would be horrified—but not surprised. His theory of alienation describes how workers in capitalist systems are disconnected from their labour, their colleagues, the process of work, and ultimately themselves. The open-plan office amplifies these alienations to deafening levels. You can’t focus on your work because Gary in sales insists on taking every call on speakerphone. You can’t connect with your colleagues because you’re too busy wondering if they’ve noticed you’ve already been to the coffee machine three times today. Even your own thoughts feel alien when they’re constantly interrupted by the sound of Karen’s particularly aggressive typing.

Where Foucault might see the open-plan office as a tool of surveillance, Marx would see it as a site of dehumanisation. The removal of walls and doors may save costs, but it also strips workers of autonomy. You have no control over your environment, no ability to retreat for privacy or focus. Instead, you’re reduced to a cog in a very noisy, very exposed machine.

And then there’s Goffman, who would likely approach the open-plan office with a mix of fascination and pity. In his dramaturgical model of social interaction, Goffman argued that life is a performance, with individuals managing impressions on the “front stage” while retreating to the “backstage” to prepare and recharge. The open-plan office, however, eliminates the backstage entirely. There’s no room to take a breather, to let your guard down, to be anything other than “on.” Every sip of coffee, every click of the mouse, every furrow of the brow becomes part of your performance.

This relentless front-stage existence is exhausting. Workers are forced to maintain a professional persona at all times, nodding enthusiastically in meetings they stopped paying attention to twenty minutes ago, or furiously typing emails they secretly know won’t be read. It’s bad theatre, performed under the harshest lighting and with the most judgmental audience imaginable. Marx might call it alienation; Foucault might call it discipline. Goffman would likely call it a tragedy.

Bourdieu, ever the realist, would be quick to point out that the open-plan office doesn’t actually flatten hierarchies, as its proponents claim. While everyone may sit together in theory, managers still have access to private meeting rooms or the ability to work remotely—luxuries previously unavailable to most employees. This access is a form of what Bourdieu called symbolic capital, a marker of status that reinforces power dynamics even in supposedly egalitarian spaces.

Employees, meanwhile, compete for their own symbolic capital through performative productivity. Staying late, answering emails at 10 p.m., and perfecting the art of “casual but focused” body language become ways to signal dedication. It’s a competition where everyone loses, except perhaps the one person who loudly announces their promotion at the Monday morning stand-up.

Weber would likely step in at this point, reminding everyone that the open-plan office is yet another example of his “iron cage” of bureaucracy. Designed for efficiency and cost-cutting, these spaces prioritise rationalisation over humanity. The irony is almost poetic: a design intended to foster creativity and collaboration instead traps workers in a rigid structure that stifles both.

And yet, the pandemic threw a wrench into this carefully crafted cage. Remote work, once considered a niche privilege, became the norm for millions. Freed from the distractions and surveillance of the open-plan office, many workers reported increased productivity and, perhaps more importantly, a sense of relief. The home office offered a true backstage, a space where workers could balance performance with authenticity.

Marx would celebrate this reclamation of autonomy, seeing it as a step away from alienation. Goffman would also applaud the restoration of the backstage, while Foucault might warn that surveillance hasn’t disappeared—it’s just moved online and made us become even more obsequious. Even Bentham might begrudgingly admit that his Panopticon doesn’t work quite as well when everyone’s camera is conveniently “broken” during Zoom meetings.

Ultimately, the open-plan office is less a triumph of modern design and more a monument to our collective willingness to endure discomfort in the name of collaboration. It’s a space where everyone is visible, yet no one truly sees each other; where hierarchies are obscured but not erased; where creativity is promised but rarely delivered.

Perhaps it’s time to leave the fishbowl behind. The future of work doesn’t need to be a Panopticon, an iron cage, or a badly staged play. It can be something quieter, more human—something with a door you can close.

Me? I loathe them with a passion.

You may also be interested in these Sociology articles:

- The Tyranny of Eye Contact: A Neurodivergent Field GuideA neurodivergent take on the social minefield of eye contact, masking, and the unfortunate realities of looking anywhere but someone’s face—including, yes, accidental boob stares.

- How Many Sociologists Does It Take to Change a Light Bulb?Ever wondered how many sociologists it takes to change a light bulb? Turns out, it’s not that simple. Dive into the philosophical chaos as academics debate the true nature of darkness, privilege, and the social construction of light.

- Yolks and Hierarchies: The Great Eggonomic DivideWhat does your choice of Easter chocolate say about class, culture, and control? A sociological deep-dive into post-Easter parenting, chocolate hierarchies, and the curious case of carob eggs.

- The Sociology of Theme Parks: Manufactured Joy and Queue-Based HierarchiesEaster at a theme park: overpriced balloons, endless queues, and manufactured joy zones. Dive into the sociology of theme parks — where capitalism meets candyfloss-fuelled chaos.

- Grounded Theory: Making It Up As You Go Along (But With Integrity)Grounded Theory: the beloved chaos engine of qualitative research. This witty deep dive explores the strange brilliance of making up your theory as you go—complete with NVivo-induced despair, reflexive diary entries, and the comforting lie of theoretical saturation.

Want More Thinky Thoughts About Society?

Still somehow intrigued by the sociology of toast crumbs, lift etiquette, or the unspoken rules of seminar seating? You may just enjoy wandering over to thinkingsociologically.com — where the sociological musings are slightly more structured but still weirdly relatable. Think of it as the thinking cousin to untypicable’s rambling uncle. Go on, have a nosey.

AJ Wright is a quiet yet incisive voice navigating the surreal world of sociology, higher education, and modern life through the unique lens of a neurodivergent mind. A tech-savvy PhD student hailing from South Yorkshire but now stationed in the flatlands of Lincolnshire, AJ writes with an irreverence that strips back the layers of academia, social norms, and the absurdities of daily life to reveal the humour lurking beneath.

As an autistic thinker, AJ’s perspective offers readers a rare blend of precision, curiosity, and wit. From dissecting the unspoken rituals of academia—like the silent war over the office thermostat—to exploring the sociology of “neurotypical small talk” and the bizarre hierarchies of campus coffee queues, AJ turns the ordinary into something both profound and hilarious.

AJ’s unassuming nature belies the sharpness of their commentary, which dives deep into the intersections of neurodiversity, tech culture, and the often-overlooked quirks of human behaviour. Whether questioning why university bureaucracy feels designed by Kafka or crafting surreal parodies of academic peer reviews, AJ writes with a balance of quiet intensity and playful absurdity that keeps readers coming back for more.

For those seeking a blog that is equal parts insightful, irreverent, and refreshingly authentic, AJ Wright provides a unique perspective that celebrates neurodiversity while poking fun at the peculiarities of the world we live in. Also a contributor at Thinking Sociologically.

Discover more from untypicable

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

[…] Sherlock, then Jeremy Bentham is his slightly diabolical predecessor, responsible for inventing the Panopticon—a circular prison where inmates are watched from a central tower. The genius? The guards don’t […]